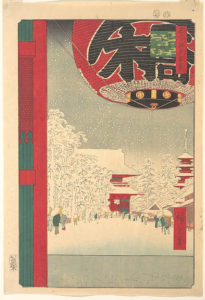

In many of his photographs, Wright appears to have actively sought out subjects and compositions evocative of the prints he so admired. The photograph of the sutra library at Chion-in is one such example. Here the library with its double-tiered roof stands at the center of the image displayed against a background of dense foliage. At center left, a substantial paper lantern towers over a group of observers, while a second group of three women stands in the foreground. Wright’s photograph recalls Hiroshige’s “Kinryūsan Temple at Asakusa,” from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. In his design, Hiroshige frames the long path toward the temple hall with a portion of the Kaminarimon, the Thunder Gate, on the left and a monumental paper lantern above.

Utagawa Hiroshige (Ando)

Kinryuzan Temple, Asakusa, No. 99 from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

1856-1859

Woodblock color print

Neither Wright’s introduction to Japanese prints, nor the exact date he began collecting them, has been precisely documented. By the time of his first trip to Japan in 1905, Wright was already an established collector of ukiyo-e prints. According to the architect the trip was made “in pursuit of the print.”

The prints that flourished in Edo period (1615-1868) Japan offered a glimpse into the lifestyle of the Japanese, depicting scenes from everyday life, courtesans and Kabuki actors, as well as popular scenic destinations. They would remain a lifelong fascination for Wright. Fundamental to the prints’ appeal to Wright was their creators’ consummate mastery of structure, their intuitive grasp of underlying form, which allowed them to capture the essence of their subject. “A Japanese artist grasps form always by reaching underneath for its geometry, never losing sight of its spiritual efficacy,” he wrote in The Japanese Print, published in 1912. “These simple colored engravings are indeed a language whose purpose is absolute beauty.”